He joined on 22nd September 1941 and spent his first sixteen weeks at RAF Henlow training to be an electrician. This turned out to be a period of intense learning, with almost daily tests or examinations. After all day in the classroom or workshops, the evenings were taken up by study or revising for the following day’s examinations, giving him little time to spend on socialising. He would have only one night a week free to visit the pub if he was lucky. After his sixteen weeks, Fred passed out of Henlow as an AC2 and was to gain his promotion to AC1 at a later stage. Even during those wartime days when skilled and trained personnel were in short supply, training standards were never relaxed to help fill the shortage.

Fred Witchell

The War Years

This is Mr. Fred Witchell’s story as told to us by Fred himself in conversations during August 2006. Fred has lived in Long Lane, Harriseahead, North Staffordshire, for many years. Some memories of his life in the RAF during WW2 are painful ones, with the loss of his friends, workmates and colleagues in the air battle over Europe.

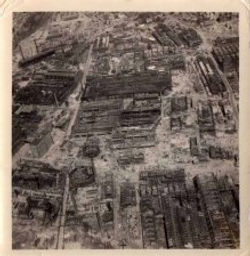

He has however, told us all that he feels able and has kindly supplied us with a wealth of photographs that he either took himself or acquired during his wartime service in RAF Bomber Command.

At the outbreak of WW2, Fred was just about to turn 17 and was still living with his parents at 30, Taunton Rd, Wallasey, a town on the Wirral which overlooks Liverpool across the River Mersey. He found employment at the Automatic Telephone Manufacturing Company in Milton Rd, Edge Hill, Liverpool, and attended technical college in the evenings.

Fred’s father was a director of International Stores, which was in direct competition with the Co-Op. With the bombing of Liverpool and its docks imminent, he decided to move into a new home at Nantwich, Cheshire. It was a large formidable country house and was to provide his family with safer surroundings away from the bombing as well as giving safe storage of a duplicate set of his company’s paperwork. We must remember that at that time, all company records were paper based and the total destruction of them during the heavy bombing would have spelt disaster for the company.

This move made life difficult for Fred, who spent most of his time on the long, arduous and unpredictable journey from his new home to work and back in those early wartime days. He was to spend most of his night school time in Liverpool, sheltering during air raids. Although in a reserved occupation, Fred eventually took the decision to join the RAF.

This is a copy of Fred’s RAF Service and Release Book

His first posting was to RAF Holme on Spalding Moor in Yorkshire. He was with 101 Squadron, and was to spend the next six months there working as an electrician on such aircraft as Wellington and Stirling bombers.

Ludford Magna

RAF Ludford Magna in Lincolnshire, was the wartime base for 101 Squadron of RAF Bomber Command and was to become Fred’s next posting, He would remain there until the end of the war. Many excellent accounts of the life and times at RAF Ludford Magna have already been written, so we will not try to repeat them here.

It is a fact however, that 101 Squadron, who’s identifying letters were SR, suffered some of the highest casualty rates for aircrew and aircraft than other squadrons within Bomber Command during WW2.

Some memories from his time there include lost friends and comrades and are hard to talk about, however it was not all sadness, there were some happier times in the squadron.

The aircraft types he worked on were Wellington, Stirling and Lancaster Bombers. When asked how the aircraft types compared, he said that without doubt the Lancaster was way out in front. The Short Stirlings differed from the others in that they had all electrically controlled systems and they were prone to failure. Fred remembers that on one occasion they had been trying to sort out a series of electrical faults on one particular aircraft. They took a meal break, but what they found when they returned afterwards was a Stirling, ‘belly’ on the ground with its undercarriage raised. Another electrical fault had decided to raise the undercarriage without human intervention while they were eating their lunch!

Repairing flack damage kept them constantly busy, forgoing meal and rest breaks to make sure that the aircraft were ready and top line for the next operation. Some of the aircraft returned so badly damaged that they were only good for spares use. How some of the aircrew managed to get these badly damaged aircraft back and land them was an incredible story of skill and heroism.

Some returned with the ‘Perspex’ cockpit canopy totally blown out or missing, injured crew members and with so much flack damage that it was a miracle the aircraft flew at all.

There were times when he had to run for cover when the German Luftwaffe dropped anti-personnel bombs on the aerodrome, only requiring small movements to set them off. The bomb disposal unit seemed to be constantly on duty.

He remembers the German fighters that would often follow the bombers back to the aerodrome to find out where the squadron was based. They took this additional opportunity to strafe the airfield and buildings with gunfire.

All the ground crews were hard working and forever on the alert, and they would secretly worry about the fate of the aircraft and the aircrews when they went on a mission, wondering which of their friends and colleagues would be lost or return to fight another day.

Fred worked on some of the more famous aircraft in WW2, one of them being Lancaster DV302, H for Harry, which went on to complete 121 missions. There were too many aircraft to mention individually but look at the photo page to see some of the others.

FIDO

FIDO was a fog dispersal system that was used at airfields during WW2 to clear fog from the runways, allowing the returning bombers to find their base and land safely. Fred remembers FIDO well; it was a series of pipes laid permanently on each side of the entire runway, which sprayed jets of lighted oil in an attempt to ‘burn off’ the fog. It worked extremely well and saved the lives of many returning aircrews. He did remark however that when FIDO was first lit, great plumes of thick black acrid smoke were produced, probably thicker than the fog itself, only clearing when the pipes got hot and vaporised the oil. As Fred put it “in a similar way to the old fashioned paraffin blowlamps”.

An incident that Fred remembers well is when an officer had noticed that the gun in the upper turret of the Lancaster would not fire in all positions and assumed that it was some sort of fault. It had to be explained to the unnamed officer, that if they did fire in all positions they would surely shoot off their own rudders from the tail plane, and not require the assistance of enemy fire to down the aircraft! The upper turret guns had to be disabled when they were turned to face either rudder, and although the officer was not aware of it, the Luftwaffe certainly were, for they used to exploit this blind spot.

Nights out were not that common, but they tried to manage at least one a week with a trip to the pubs in Louth. If any Americans came into the pub they were drinking in, they would quickly leave, for it usually meant arguments followed by a fight breaking out. On a few occasions, they missed the liberty bus back to the base and had to walk the whole 9 miles! Celebrations on VE night meant a few drinks at the pub in Ludford Magna village.

With the bombing campaign in Europe ending, the war in the Far East was still going on with no end in sight. Fred and his ground crew colleagues were ordered to report to Blackpool to be re-assigned to the Army, with the intention of sending them out to the Far East to continue the fight. Fred managed to delay reporting to Blackpool by a few weeks. By the time he eventually got there, the war with Japan was coming to an end and so he was to remain with the RAF until his discharge on 19th November 1946.

Fred tells us that he would have liked to have remained in the RAF and make it his career, but being newly married, he had a wife to consider. After talking it over, it was decided that a life living at various RAF stations throughout the world would not be right for them to start and bring up a family.

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

Life Before and After The War

The earliest photo of Fred, seen here at the age of one sitting on his mother Rose’s knee. Fred’s father Harry is standing at the rear, with sister Joan Elizabeth. Sister Phyllis Irene is sitting at the front. This photo was taken sometime during late 1923.

Fred was born on 22 October 1922 to parents Harry and Rose Witchell, who were already parents to his older sisters Phyllis Irene and Joan Elizabeth. His father was no stranger to conflict, for he had fought alongside countless others on the battlefields of WW1 as an officer in the 11th Hussars. Fred spent most of his early life living at 30, Taunton Road, Wallasey, The Wirral, Cheshire.

The following are Fred’s own words – “I first started to walk out with Edna when I was only 12 years old. She lived with her auntie and uncle just across the road from us at number 33 Taunton Rd. Edna’s mother had died soon after she had been born. We used to go to the pictures in Wallasey on Saturday afternoons and when my parents and Edna’s guardians allowed, we would walk around together in the evenings. Edna took up piano lessons, which meant that on some evenings I had to wait around for her while she practiced, all in the hope that it would not be too late to go for a walk. I got to know Edna’s family really well and spent a lot of time with them. It was about a year before the outbreak of the war that Edna started to take a keen interest in dancing. It was an interest that I didn’t share with Edna, for my interests were football, cycling and sport in general. During this time, Edna met a lad called Bill, and she began to regularly go dancing with him. Eventually Edna and Bill started to go out together, I was heartbroken of course.

Soon after the war began, Bill was called up and went into the RAF, his posting was to South Africa. I eventually joined the RAF myself and after training, was posted to Holme on Spalding Moor. On the few occasions that I was off duty in the evenings, I would write home to my parents in Nantwich, Cheshire. After a time, I started to wonder about Edna, did she still live in Wallasey and how was she? I wrote her a letter in the hope that she would receive it. Weeks went by with no reply, but I waited patiently, eventually I received a letter from Edna. She wrote that she was well and enjoying her life in spite of the war and that she would be pleased see me on my next leave. My leave duly arrived and I could not wait to get to Wallasey to see her.

When I eventually arrived, Edna’s family greeted me with open arms. I remember thinking how well she looked and that she was as pretty as ever. During the course of the evening, Edna appeared to be quite agitated and disappeared into the kitchen to help with the dinner. Her uncle took this opportunity to tell me the reason for Edna’s distress, for she had only that morning, received a letter from Bill saying that their relationship was over because he had met someone else in South Africa. I was secretly glad for myself, but sad for Edna who was obviously distressed by the news.

From that night onwards, my relationship with Edna began again. I was to spend the rest of the war knowing that Edna was waiting for me at home.

We married just after the war and set up home in a bungalow at Ormskirk, 9 miles north east of Liverpool. I went back to work for the Automatic Telephone Company in Liverpool who were obliged to offer my pre-war job back to me on discharge from the RAF in November 1946, a job that I came to hate. I persuaded my father to let us move into his large house with him in Nantwich, where I started to work for myself as, would you believe it, a pig breeder. This did not please my father, but I continued for 3 to 4 years and I had over 200 pigs.

The time then came for my father to retire which meant that the house was too large for us to maintain. By this time, we also had our young daughter Diana to consider. I gave up pig breeding and went into the world of insurance. We would move over the coming years to Crewe and then to Nantwich to be wherever my work took us.

It was during 1982 that Edna passed away. I decided to move after had Edna passed away and bought the house Long Lane, Harriseahead, North Staffordshire where I still live today.”